- Home

Page 3

Page 3

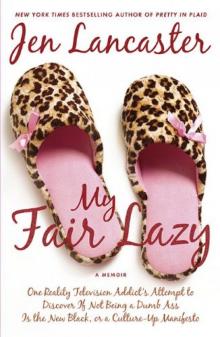

My Fair Lazy: One Reality Television Addict's Attempt to Discover

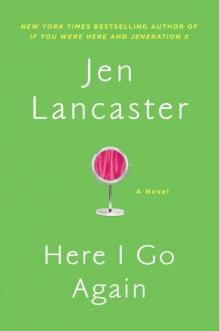

My Fair Lazy: One Reality Television Addict's Attempt to Discover Here I Go Again: A Novel

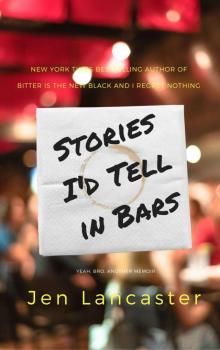

Here I Go Again: A Novel Stories I'd Tell in Bars

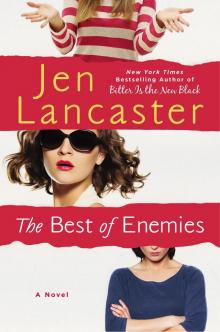

Stories I'd Tell in Bars The Best of Enemies

The Best of Enemies Bright Lights, Big Ass

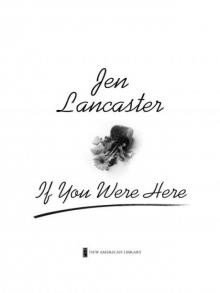

Bright Lights, Big Ass If You Were Here

If You Were Here Pretty in Plaid: A Life, A Witch, and a Wardrobe

Pretty in Plaid: A Life, A Witch, and a Wardrobe Twisted Sisters

Twisted Sisters Such a pretty fat: one narcissist's quest to discover if her life makes her ass look big

Such a pretty fat: one narcissist's quest to discover if her life makes her ass look big By the Numbers

By the Numbers Bright Lights, Big Ass: A Self-Indulgent, Surly, Ex-Sorority Girl's Guide to Why it Often Sucks in theCity, or Who are These Idiots and Why Do They All Live Next Door to Me?

Bright Lights, Big Ass: A Self-Indulgent, Surly, Ex-Sorority Girl's Guide to Why it Often Sucks in theCity, or Who are These Idiots and Why Do They All Live Next Door to Me? Jeneration X: One Reluctant Adult's Attempt to Unarrest Her Arrested Development

Jeneration X: One Reluctant Adult's Attempt to Unarrest Her Arrested Development My Fair Lazy: One Reality Television Addict's Attempt to Discover If Not Being A Dumb Ass Is the New Black, or, a Culture-Up Manifesto

My Fair Lazy: One Reality Television Addict's Attempt to Discover If Not Being A Dumb Ass Is the New Black, or, a Culture-Up Manifesto Bitter is the New Black

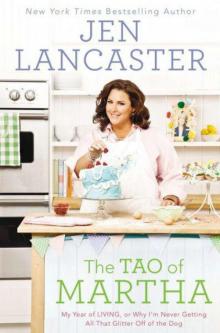

Bitter is the New Black The Tao of Martha: My Year of LIVING

The Tao of Martha: My Year of LIVING Bitter is the New Black : Confessions of a Condescending, Egomaniacal, Self-Centered Smartass,Or, Why You Should Never Carry A Prada Bag to the Unemployment Office

Bitter is the New Black : Confessions of a Condescending, Egomaniacal, Self-Centered Smartass,Or, Why You Should Never Carry A Prada Bag to the Unemployment Office Pretty in Plaid: A Life, A Witch, and a Wardrobe, or, the Wonder Years Before the Condescending,Egomaniacal, Self-Centered Smart-Ass Phase

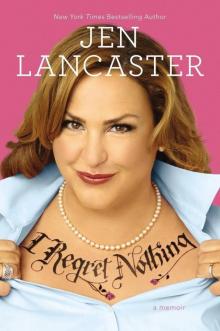

Pretty in Plaid: A Life, A Witch, and a Wardrobe, or, the Wonder Years Before the Condescending,Egomaniacal, Self-Centered Smart-Ass Phase I Regret Nothing: A Memoir

I Regret Nothing: A Memoir If You Were Here: A Novel

If You Were Here: A Novel The Tao of Martha: My Year of LIVING; Or, Why I'm Never Getting All That Glitter Off of the Dog

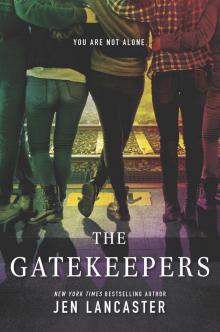

The Tao of Martha: My Year of LIVING; Or, Why I'm Never Getting All That Glitter Off of the Dog The Gatekeepers

The Gatekeepers